How AI changes digital product prototyping

From paper sketches to functional software demos, AI is transforming how digital products are prototyped—faster, smarter, and often with fewer technical barriers.

Everybody roughly understands what a prototype is, but the term means different things to different audiences. A developer may call a test program a prototype. An industrial engineer may call a 3D print a prototype. And a designer may use the term to refer to various artifacts, from paper storyboards to graphical designs of an app layout.

According to the seminal article by Stephanie Houde and Charles Hill, a prototype is a representation of a design idea in any medium. It is a core means to explore and express designs. In other words, it’s any process that aims at making sure, early on and with low investment, that a team is building the right thing.

Traditionally, prototyping has been associated with early-stage designs in low-fidelity , but also with creativity and innovation. Historically famous prototypes include Douglas Englebart’s computer mouse—which had wheels—, a paper sketch of Twitter, and different Palm prototypes (the handheld computer that was popular in the late 1990s and early 2000s), the first of which was simply a wooden block used by the founder to test weight and ergonomics.

When it comes to digital product prototyping, recent advances in generative AI, and especially large language models (LLMs), are exhibiting a profound impact. Unlike the first versions, such models currently generate high-quality images, which can be included in designs, and excel at producing code, which can serve as basis for a prototype website or a functional simple demo of a digital product. Moreover, a plethora of content creation products derived from such LLMs is populating the prototyping ecosystem.

The bottom line: in today’s world, navigating the ecosystem of AI tools confidently is a required skill in prototyping.

This post explores how advances in AI are influencing various traditional prototyping techniques, illustrating each point with examples created by students during the course Data-Driven Prototyping with AI. This elective, offered to Esade students across several MSc programs—including Innovation, Marketing, International Management, Finance, and Sustainability—provides a hands-on opportunity to practice a prototyping mindset, even for students without a previous technical background, especially as in coding.

Paper sketches and storyboards

The simplest form of prototyping a digital product is paper sketching, which involves techniques like simply drawing the designs for initial inspiration and commentary about the look and feel and the app flow. A special case of paper sketch is a storyboard, which depicts product journeys to contextualize the use of the product and potentially showing its major role or impact in the life of a user.

The possibilities of AI in this area include inputting the low-fidelity hand-drawn designs to generate high-fidelity depictions, asking an AI system to directly generate a storyboard from a script, or even having it suggest the scripts. The following image shows a student storyboard of an AI powered feature for an art store app:

The ability to generate storyboards from a provided script in a desired style within a short time represents a complement to traditional storyboarding. It allows for testing different and potentially more ideas. As for their limitations, storyboards are difficult to edit once produced, and they still exhibit problems with generated text. It also means the designer skips some creative decisions and is “anchored” to the design criteria of the AI’s black box.

Wireframe and mockup prototyping

Wireframes are low-fidelity representations of a user interface using simple shapes and lines to outline the layout and placement of the elements, while deliberately avoiding details such as specific text or images. Their goal is to get the interface right without distractions from visual design. They can be produced with pen and paper, presentation software (such as PowerPoint, Canva, Miro), or with specific wireframe software such as Balsamiq. This technique is useful to focus on the overall structure and functionality of the interface before considering details such as fonts, colors, and images.

Compared to a wireframe, a mockup is a higher fidelity representation of a user interface, with realistic colors, fonts and icons, and possibly with some interactivity. The look and feel may be very close to the final product, but it is not functional software yet. Mockups are used in a phase where discussing the specific look and feel matters. Professional software for digital prototyping includes Principle, Sketch, and Marvel.

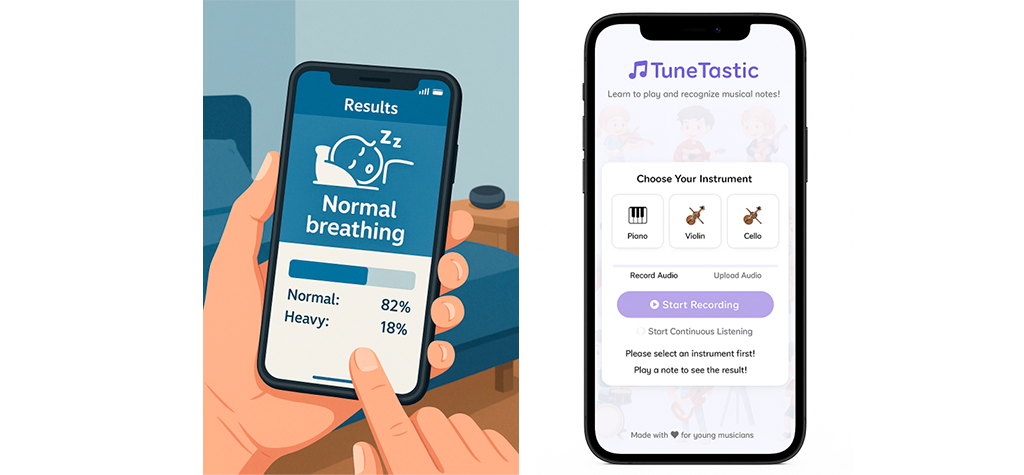

The possibilities offered by AI in this area include producing wireframes from instructions, as well as mockups or materials at any level of intermediate fidelity. As an example, in the left image below we see a concept of a screen design for a sleep monitoring app. The design is probably at a fidelity level in between a wireframe and a mockup.

As another possibility of prototyping with AI, code generation platforms like Lovable or Bolt are useful to create an initial app design that, in the first iterations, essentially plays the same role as a mockup. The image above on the right displays another example produced by a student.

These strategies offer users the possibility to create materials faster and with higher fidelity than traditional tools. Also, in the case of code assistants, it produces a functional app that can be shared and extended. On the downside, images produced with GenAI can be difficult to edit when it comes to adding specific details. In the case of code generated with an assistant like Lovable, the output is editable, but doing so requires coding knowledge. Users with little coding experience may find themselves blocked when the produced design does not match the instructions. However, some users relearn new strategies. As some students reported, “prototyping is non-linear: sometimes re-building is faster than debugging.”

Video prototyping, Wizard of Oz prototyping

In video prototyping, we start from any prototyping medium—such as paper sketches or digital mockups—and ‘animate’ it using video to create the illusion of interaction with the product for the viewer.

A related technique, Wizard of Oz prototyping, simulates the behavior of a complex system or feature, but the real functionality is replaced by a human behind the scenes who (like in the Wizard of Oz movie) controls the ‘fake’ system’s responses. This technique is useful to validate product acceptance before implementing the full system. As an example, consider a team building an app that gives nutritional information about a food item based on a picture. To test the concept with users early—even before implementing the image recognition system—they can use a Wizard of Oz prototype as a special case of video prototyping.

An interesting use of AI in this area is precisely to bridge the gap between a fake video and the real functionality. As more and more AI functionalities become available through APIs, software libraries, and demos, we can increasingly replace simulated interactions with actual working features. Even if the AI tool isn’t fully integrated, its output can still deliver genuine results.

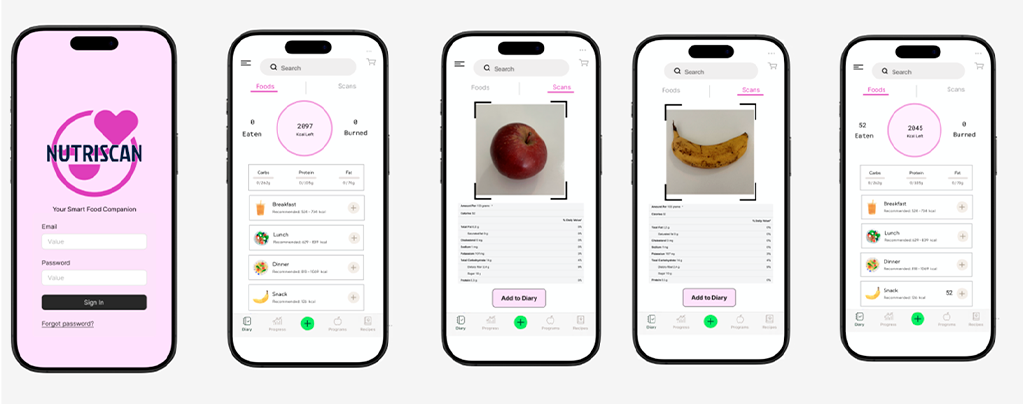

For example, by exploiting a demo platform such as the Teachable Machine, we can train a real machine learning model—for instance, for image recognition—and incorporate the real recognition result in a video prototype. The example below shows a student prototype of a nutritional info app that uses the Teachable Machine to recognize and classify images and inserts the resulting output into a prototype.

In this case, the main advantage of using AI is that it enriches traditional prototypes with elements of real functionality. The main disadvantage is that, if communicated poorly or to the wrong audiences, it can create the illusion that the product is close to being ready and lead to wrong development or resource allocation decisions.

Software prototyping

A software prototype is a real piece of software—only more basic than the final product or containing only a subset of its features. It is useful when it comes to making implementation decisions, or when it is important to test functionality.

Software prototypes were traditionally considered higher-fidelity and left for late phases of design. However, programming is becoming increasingly easier thanks to high-level languages, packaged libraries, APIs implementing third-party functionality, and AI code generation. As a result, probably we need to redefine this vision around the cost of software prototypes.

Specifically, using AI in software prototyping has three possible approaches. The first is incorporating AI functionality into a prototype through libraries or APIs. The second is using AI to assist with code generation. The third is using generative AI as “instruction models” to perform actions on demand based on language prompts (instead of implementing the code manually).

The next image shows a student prototype illustrating the first approach: a third-party barcode recognition functionality was integrated into an app by just importing a public JavaScript library.

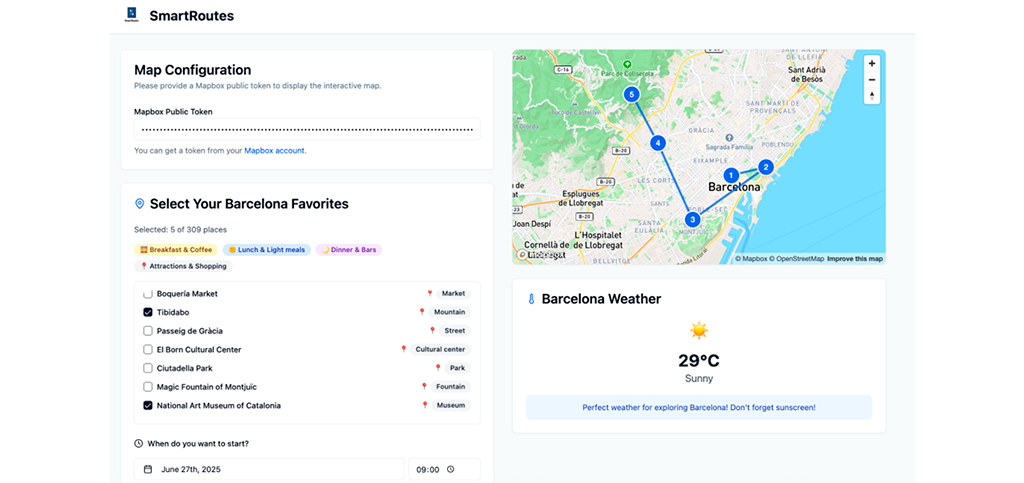

The second approach (using AI to assist in code generation) is exemplified by this other student prototype of a tool to mark favorite places in a city and suggest smart routes. The application was generated by Lovable but adding a significant amount of domain knowledge.

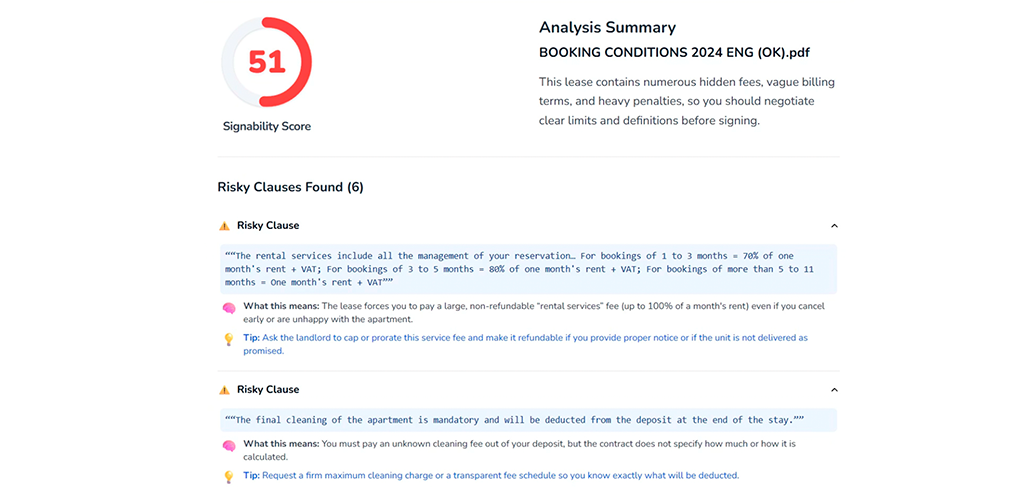

The third approach (using AI as instruction models) was implemented in e next student prototype. The app is a signability checker that reads rental contracts and warns about risky clauses. The specific functionality is implemented by making a call to the OpenAI API. In this domain-specific example, designing a detained prompt was crucial. As students noted, “The prompt […] defines how the product behaves. Minor tweaks dramatically changed outcomes, which taught us to treat prompt design like programming.”

The productivity increase in coding thanks to AI is well-documented, placing AI as a strong driver in software prototyping. This is both for developers who get “augmented” by coding copilots as well as for roles with less experience in coding, which can resort to app generation tools. The advantages and drawbacks of this approach were discussed in a previous post.

Design fictions

Design fiction is the practice of creating tangible and evocative prototypes from possible near futures. It allows for new product discoveries and helps to represent the consequences of the technology. It is a valid “prototyping technique”, as its process shares many similarities with traditional prototyping—particularly its focus on reducing risk and serving as a basis for strategic discussion, potentially at a strategic level.

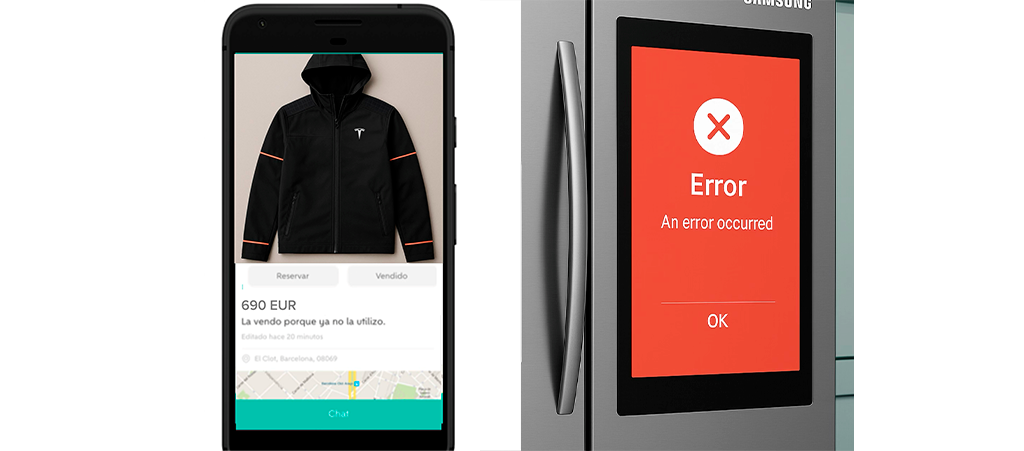

Using an exercise proposed in The Manual of Design Fiction, students imagined possible new products outside of their usual context—such as a Smart Mirror or a Tesla-connected jacket, depicted in the image below.

It is undoubtable that the AI image generation capabilities are game-changing in producing such fictional materials from instructions. However, strictly speaking, design fiction is not so much about showcasing a potential new product, but about giving a provocative example in a mundane context. Again, common LLMs are impressive at generating images in a new situation. The following examples, closer to the real aim of design fiction, were generated from student submissions using ChatGPT (a user who sells the Tesla jacket online or a smart fridge that gets blocked because of an error):

A possible risk here is that users may reduce the whole design function process to just the generation phase, whereas design fiction encompasses several stages and dimensions. Also, many famous examples of design fiction gravitate around other formats, such as provocative videos or physical objects. While AI can assist in generating ideas, at the end of the day design fiction requires some “artistic” skills that need to be provided by humans.

Final remarks

A key observation is that many of the examples of prototypes produced during this course could not have been made two years ago – because the tools used had not been released or the capabilities of image and text generation of LLMs were less powerful. Perhaps that is the best proof of how AI impacts the traditional prototyping techniques.

Making prototyping easier will have profound consequences for how companies innovate. In his work Cultures of Prototyping, Michael Schrage argues that organizations seeking to build better products must first learn to build better prototypes. A company’s innovation culture can be revealed through the quality of its prototypes. Today, as AI becomes inseparable from the prototyping process, the way companies adopt AI in prototyping will be a strong signal for their capacity for innovation.

Note: Thanks to all the students who produced and gave consent for showcasing the examples.

Header image: Yasmin Dwiputri & Data Hazards Project / AI across industries. / Licenced by CC-BY 4.0

Senior Lecturer, Department of Operations, Innovation and Data Sciences at Esade

View profile- Compartir en Twitter

- Compartir en Linked in

- Compartir en Facebook

- Compartir en Whatsapp Compartir en Whatsapp

- Compartir en e-Mail

Do you want to receive the Do Better newsletter?

Subscribe to receive our featured content in your inbox.