Quo Vadis, Higher Education?

Higher education faces an accumulation of challenges related to supply, demand, and educational content and processes. A reflection that calls upon all universities is necessary.

The long-term reflection on Esade's future, prompted by the institution's new general director, provides an opportunity to contemplate the future of higher education and how to address the significant challenges it faces. We find ourselves at a crossroads, perhaps on the verge of a major disruption, similar to those that have reshaped other sectors. It is not necessarily—although one can never be certain—about the emergence of new developments. Rather, it is the accumulation of existing elements whose impact will be felt more strongly in the coming years.

Universities are, potentially, remarkable educational ecosystems involving a wide range of stakeholders, making them deeply interconnected with the societies in which they operate.

Moreover, higher education is a growing sector, at least for institutions of a certain level of quality. Leading universities continue to expand their academic offerings, increase their student bodies, broaden the age range of learners in their classrooms, and invest in larger campuses and improved facilities.

This growth may give the impression that no major transformations are required. It might seem sufficient to seize opportunities and adapt to the rapidly changing times without venturing much further. However, we believe that a profound reflection is essential. This reflection primarily concerns undergraduate programs, though it is relevant, to varying degrees, across the entire academic offering. We identify three major areas of challenge that are deeply interconnected:

- It is unclear what should happen in the classroom today. In many cases, the teacher-student relationship in the classroom no longer mediates the student's primary learning process. This is due to a series of changes, notably generational shifts and the significant lack of attention many students exhibit during class, exacerbated by the distracting use of digital devices and the easy access to online educational materials.

- It is also unclear what unique value higher education truly provides. The absence of a profound reflection on what it means to educate in today's world explains why one of the main drivers of academic program reform is often student demands or the needs of companies. As a result, short-term dynamics dominate the university landscape, to the detriment of reflection on the ultimate purpose of education, the participation of stakeholders beyond the corporate sector, and the pursuit of a more holistic preparation that extends beyond mere "customer satisfaction."

- The relationship between technology and education is also unclear. Gradually, technology is becoming an integral part of university teaching. The emergence of artificial intelligence represents a significant leap forward in this direction. However, the primary focus of pedagogical departments seems to center around selecting the most suitable educational tools or platforms. Yet, these tools carry the risk of stripping universities of their greatest value-added areas, as they delegate the design, control, and data of the learning process to the tech companies that develop them.

In other words, and in a more systematic way, we can say that higher education today faces fundamental challenges related to supply (who the educators are), demand (who the learners are and what dynamics they follow), and content or process (what should be taught and how). Let’s take a closer look at each of these three areas:

1. Challenges in supply

There are three key risks related to the supply of higher education. The first concerns the number and characteristics of universities operating in the sector. The second involves high-tech educational platforms. The third pertains to the relationship between the teaching staff and the institution's educational mission.

1.1 A growing supply of universities

The higher education sector has become highly dynamic and competitive. By its nature, it is a global sector, driven by the interconnectedness of the global economy and society, despite recent trends toward protectionism or reshoring. Nevertheless, there remains a strong local component, and regional or continental trends continue to be significant. Globally, there is increasing demand for high-quality education in a market where the most talented, ambitious, and well-resourced students move freely across borders. This market potential attracts new players to the sector and drives existing institutions to expand and strengthen their positions. Universities no longer hold a monopoly on higher education.

Within this expansion of the university supply, we can distinguish between two key trends. First, the creation of new universities or the national and international expansion of existing ones. Second, the emergence of non-traditional educational actors seeking to establish a relevant position in the sector. This phenomenon has been evident for some time, with the rise of online educational platforms (Duolingo, Udemy, etc.), specialized educational centers (Singularity University, Kaospilot, etc.), and entities from related sectors such as publishing or cultural organizations (e.g., Grupo Planeta in Spain).

In addition, the organizations that manage university rankings are becoming increasingly influential—and this influence represents a thriving business. By ranking universities primarily based on their research output and the post-graduation salaries of their alumni, they create powerful incentives so that the reputation they bestow (and its instant monetization) is not directly related to the quality of the educational experience.

A related phenomenon is the financialization of higher education. In recent years, the sector has seen the entry of financial actors, investment funds, and companies aiming to maximize returns by either establishing new universities or acquiring stakes in existing ones. This dynamic places pressure on the sector in terms of both its goals and its educational offerings due to the significant economic influence these new players wield.

Finally, there is the emergence of a different class of competitors—not institutions seeking to attract students, but companies offering programs and technologies aimed at being implemented within existing institutions. We will address these later in more detail.

As an example, consider the Madrid region, where no fewer than 28 universities of various sizes currently operate. These institutions can be categorized into public universities, private secular universities, and private universities with Catholic or Christian inspiration. This number may continue to rise in the coming years.

1.2 Technological platforms transforming the learning relationship

The second challenge is the emergence of AI-based technological platforms offering their products to traditional universities. Many of these platforms are owned by tech companies, though some universities—such as Stanford, Imperial College, and others (mainly in the US)—are developing their own AI-based educational products and programs.

The primary risk here lies in the shift in the mediation of the learning relationship between professors and students. Historically, this relationship has been the core value proposition of universities: professors, through their expertise, guided students in their learning process. The integration of high-tech educational platforms fundamentally alters this dynamic. Although these platforms may require a significant initial effort from students to adapt, their potential for personalization, immediate feedback, and reward mechanisms—likely to become increasingly sophisticated—can surpass many traditional teaching methods. The role of the professor is gradually shifting toward that of a facilitator, curator, or mentor, rather than being the central figure in the learning process. For many, this transformation is seen as inevitable.

The concern is that the university’s key value-added function could become externalized to these platforms, which would also control all student learning data. This raises the question of whether enough thought has been given to what the true value proposition of universities should be—and where it will reside—in a context where the technologization and cost of high-quality education are both expected to rise.

1.3 The relationship between faculty and the educational mission

The internationalization of academic staff is a response to the growing globalization of the higher education sector. It also promotes the incorporation of talent and increases the diversity of departments. This trend is accompanied by a stronger emphasis on research in academic careers, as well as more international professional trajectories. However, there is a risk that the connection between professors and the universities that employ them may weaken. Teaching is no longer the primary activity of many faculty members, nor the one that most advances their careers. Instead, recognition from academic journals or international conferences—essentially, peer approval—often outweighs recognition from their own institutions. This dynamic is sometimes encouraged by the universities themselves.

2. Challenges in demand

When it comes to demand, two key risks can be identified: the evolution of the student population and students' willingness to engage in learning.

2.1 Evolution of the student population

The sharp decline in birth rates experienced by many countries—particularly Western nations—over the past two decades is a well-known trend. However, this demographic shift does not impact all universities equally. The most prestigious institutions continue to grow their student bodies, in some cases offsetting the decrease in local students by attracting a larger number of international students. In fact, a significant increase in the university-age population is expected in major Asian and African countries.

Although this growth in student numbers may persist in the short and medium term, it is not without risks. The gradual reduction of local students will inevitably create a more competitive landscape for all actors in the sector. The increase in international students—especially those from less developed countries—will last only until their home countries can develop high-quality education systems of their own. In this context, the slower economic dynamism of Europe and the global economic shift toward other regions present medium- and long-term risks for the European higher education sector.

2.2 Students' willingness to learn

In the complex technological and professional landscape we are navigating, one might assume that optimizing students' learning experiences at university is a top priority. However, this does not seem to be the case. The widespread use of digital devices in the classroom (laptops, tablets, smartphones) has led to a significant decline in students' ability to focus and maintain attention. If a class is even slightly unengaging, the temptation to disconnect is strong, creating a domino effect among students. A master's student at Esade recently commented on this phenomenon, highlighting how easily distraction spreads in the classroom:

I also really enjoyed and support the “no phones or laptop” policy. In other classes, many students (sometimes including myself) are completely disconnected for the whole duration of the class, applying to jobs on their laptops or scrolling through Instagram on their phones. Not being allowed to do so forces students to listen and engage in the class to a certain extent. In an age where our attention spans are shortening and we constantly have to occupy our minds with multiple things at once, spending 3 hours in class with no phones or laptops is a great positive for all of us.

This lack of attention is likely the result of several factors, including the fact that nearly any content can now be found online (or through AI systems like ChatGPT) and the prevalence of more horizontal, self-guided study methods that students have increasingly embraced. It is essential to gain a deeper understanding of the cultural and psychological profile of students entering university. In this regard, fostering a pedagogical dialogue between universities and secondary education institutions—something that currently seems lacking—would be highly beneficial.

3. Challenges in content or process

These challenges concern the ultimate purpose of education and the specific content of academic programs.

3.1 The ultimate purpose of education

Education—rooted in its etymology e-ducare—was conceived to cultivate and bring forth the best in the human being. Philosopher Javier Gomá argues that universities should shape citizens who can recognize the dignity of others and also produce competent professionals, but if a choice must be made, the former purpose should always take precedence. However, higher education today seems to be heading in a different direction. As noted earlier, designing curricula based on the current needs of companies or market signals—such as university rankings—results in short-term approaches.

The changing role of professors, from being central figures in the learning process to becoming facilitators or curators, is another step along this path. While personalizing education and giving students more autonomy in their learning journey offers many positive benefits that should be embraced, education is more than that. It has a social dimension and serves the common good, which may not always be immediately appreciated by everyone. If students are positioned as the primary leaders of their learning, as some educational trends advocate, there is a risk that professors may merely follow the trends that students absorb from social media and other information sources.

A variation of this phenomenon occurs when the professor's role is to guide students' use of high-tech educational platforms. In this case, leadership is effectively transferred to the engineers—often from the US or other countries—who design these tools, embedding their own values and worldview into them, and building the loyalty of their student users.

3.2 Content of academic programs

Designing academic programs is a complex task, particularly when the impact of new technologies on economic activity, social relationships, and, consequently, the role of education itself remains uncertain.

It seems clear that technological change will profoundly affect what we need to learn. As David Brooks points out, the current emphasis on cognitive learning—focused on specialization, rationality, and measurable outcomes—contributes to some of the most serious problems in society. Moreover, cognitive knowledge is the most easily replaceable by artificial intelligence. In contrast, relational and holistic knowledge—centered on how different spheres of reality interconnect—could have a more enduring value. Brooks' vision underscores this idea: “We want a society led by intelligent people, yes, but also by those who are wise, insightful, curious, empathetic, resilient, and committed to the common good.”

Furthermore, it is notable that despite the growing complexity of the world and the immense social, political, and environmental challenges we face, these issues appear to be insufficiently reflected in curriculum reforms and classroom discussions. While media discourse saturates us with these global challenges, they often seem disconnected from our educational responsibilities. There appears to be a gap between the urgency of these issues and the depth with which they are addressed in academic environments.

Implications for higher education

The previous reflection leads us to the following conclusions:

- University education is moving along a path where technical and technological aspects are increasingly dominant. This shift creates both opportunities and risks. On the one hand, the operational model of universities remains relatively traditional. On the other hand, it is essential to consider how this transformation affects every element of the educational value chain.

- In today’s more open and globalized educational landscape, education tends to become commoditized: technology, professors, and students engage in a marketplace where they buy and sell essentially the same products. The differentiation between institutions follows the same dynamics as consumer products. Within this market, there is room for educational offerings with purpose or that meet higher psychological needs, though these often remain secondary elements that add value without fundamentally redefining how we view the academic or business world.

- The primary strategic risk for universities without a solid educational model is the outsourcing of their core value proposition: the mediation of the learning relationship between professor and student. The widespread adoption of AI-based educational platforms could relegate universities to being merely the physical or virtual spaces where certain types of learning occur—contributing to and complementing the student experience, but not shaping it at its core. This approach may allow institutions to grow and remain relevant, but in doing so, it may hollow out their foundational purpose.

- We must remember that higher education was originally created with a clear mission: to foster the holistic development of individuals and contribute to the common good. This need persists today—it is something the market itself requires but, more importantly, something society as a whole demands. Paradoxically, the short-term incentives characteristic of the market cannot independently fulfill this mission. There will always be a place for a broader vision of education, but this requires universities to continuously work on and update their why and for what, cultivating a cohesive and engaged educational community—comprising faculty, students, and administrative staff—that is aligned with the institution’s project.

- In an increasingly interconnected world with global challenges, horizontal educational alliances (with other universities) and vertical partnerships (with other social and educational actors) become invaluable assets.

Esade's role

In the context we have described, Esade holds two key advantages and one challenge to overcome.

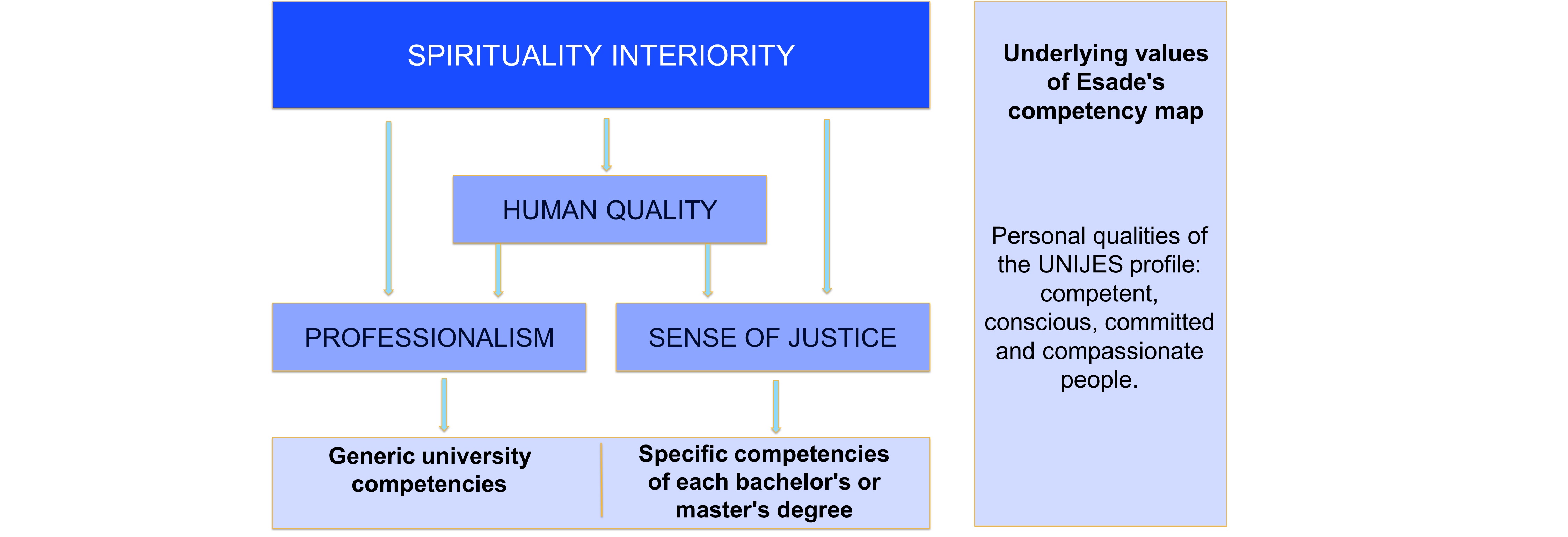

The first advantage is that the institution was founded with a clear purpose: to integrate, from a foundation of spiritual reflection and inner depth, excellence in business and leadership education with the holistic development of students, service to the common good, and a commitment to justice. This is embodied in the "4 Cs" model: the formation of individuals who are conscious, competent, compassionate, and committed. This legacy—illustrated in the figure below—has been passed down throughout Esade’s nearly seventy years of existence. Many faculty members and non-teaching staff are deeply inspired by these values, and the institution's humanistic and Christian roots are an integral part of its identity. Additionally, Esade is part of UNIJES, an international university network—also encompassing educational and social initiatives—that shares this vision of education, commonly known as Ignatian pedagogy.

The second advantage is the strong demand for a higher education model that places people at the center. Various international institutions, some of the most recent trends in business management (humanistic leadership, the IDGs, etc.), and the profiles of the students entering our classrooms point in the same direction as our pedagogical model. The inspiring aspect of our educational project is that it integrates a broader and deeper perspective on education than is found in many other institutions and requires the collaboration of the entire educational community. It is not just about delivering content but about educating and guiding meaningful student journeys that foster success both personally and professionally and empower students to lead lives of purpose, committed to building a more fraternal and just society.

In transmitting this culture, specific individuals—faculty members and staff, some of whom are Jesuits or former Jesuits—have played a fundamental role in shaping our institutional culture. However, continuous efforts to adapt and anticipate change in a rapidly evolving environment are essential. The challenge is to transmit this educational philosophy in an even more institutional and comprehensive way so that it permeates the entire organization and all its educational activities.

The challenges and opportunities outlined in this document suggest that, in addition to reconfiguring the content and methods of university learning, a deeper reflection on the meaning and potential of our educational work is necessary. This document aims to be a first step in that direction. The new challenges do not undermine the value of our educational model but encourage us to deepen it and make it truly impactful. This is the greatest assurance of success for Esade’s future and a defining factor that can significantly differentiate us from other educational institutions.

Associate Professor, Department of Society, Politics and Sustainability at Esade

View profile

- Compartir en Twitter

- Compartir en Linked in

- Compartir en Facebook

- Compartir en Whatsapp Compartir en Whatsapp

- Compartir en e-Mail

Do you want to receive the Do Better newsletter?

Subscribe to receive our featured content in your inbox.