Unlocking the potential of carbon markets: Challenges and opportunities

International emissions trading has considerable potential to incentivize a greener economy. However, for it to be truly effective in reducing global emissions, several key challenges must be addressed.

Carbon markets emerged as a strategic response to the growing concerns over climate change and the need for effective mechanisms to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The concept of carbon trading was first introduced under the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, which established structures for trading emissions allowances internationally. These mechanisms paved the way for modern carbon markets by allowing countries to buy and sell emissions reductions through Emissions Trading Systems.

The Paris Agreement in 2015, which replaced the Kyoto Protocol, has been a critical catalyst in expanding carbon markets to a global scale, aiming to limit global warming to 1.5ºC. By setting ambitious emissions targets for 2030, the Paris Agreement has driven international cooperation under Article 6, which established frameworks for cross-border trading of emissions reductions. This framework promotes standardized global carbon markets to enhance the efficiency and scale of emissions reduction efforts and is one of the key topics of discussion in COP29, currently taking place in Baku.

A market mechanism for a greener economy

The purpose of carbon markets is twofold: first, to create economic incentives that encourage industries to reduce emissions by placing a financial cost on carbon; and second, to attract investments in low-carbon technologies and carbon capture solutions. Economically, carbon pricing seeks to internalize the negative externalities of GHG emissions, allowing the carbon price to reflect the societal cost of emissions. This approach supports the transition to a greener economy by promoting cost-effective emissions reductions and fostering innovation in sustainable alternatives.

Some companies may generate surplus emissions reductions, which they can sell as credits to others seeking to meet reduction goals

Buyers of carbon credits are typically companies or individuals who produce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and seek to offset or "neutralize" their environmental impact. On the other hand, sellers of carbon credits are companies or projects that implement GHG-reducing or carbon-sequestering solutions, such as renewable energy installations, carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology, and nature-based projects like reforestation, afforestation, and sustainable land or ocean management. For example, companies that transition to renewable energy or adopt energy-efficient systems may generate surplus emissions reductions, which they can sell as credits to others seeking to meet emissions reduction goals.

Carbon credits are traded in carbon markets, which are divided into compliance and voluntary markets. Compliance markets are government-regulated and are driven by mandates that require companies to reduce emissions, whereas voluntary markets are used by companies and individuals who choose to offset emissions beyond regulatory requirements. Voluntary markets allow greater flexibility, especially for organizations looking to exceed minimum standards or address sectors where immediate, substantial emissions reductions are technologically challenging.

Proven high potential

The European Union’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), the world’s largest compliance market, has seen significant growth in recent years (see Figure 1). As of 2023, estimates place the global carbon trading market’s value at over $900 billion, with the EU ETS alone accounting for a substantial portion of this market. Reports suggest that the EU ETS comprises between 75% (according to Bloomberg) and 87% (according to Statista) of the global carbon market’s total value, underscoring its dominant role in emissions trading and its critical impact on carbon pricing worldwide.

Figure 1. Value of the carbon market worldwide. Source: Statista, 2024.

Carbon markets are an essential financial mechanism that supports efficient climate policy by setting a price on carbon emissions, which incentivizes emissions reductions at the lowest possible cost. By enabling reductions to take place where they are most cost-effective, carbon markets allow companies flexibility to choose the most economical solutions to meet emissions targets. These markets also offer growth opportunities in critical areas, such as advancing carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies, scaling up renewable energy sources, and promoting nature-based solutions like reforestation.

The central question is whether the carbon market facilitates real reductions in carbon emissions or merely enables offsetting

In addition, carbon markets facilitate the implementation of carbon pricing mechanisms, and encourage innovation through new financing models, certification standards, and digital platforms that enhance transparency and efficiency. However, realizing these opportunities requires addressing several challenges, such as effectiveness in GHG reduction, ensuring high-quality carbon credits, avoiding double counting, maintaining price stability, and establishing reliable verification systems, which are crucial for the long-term success and credibility of carbon markets.

The challenges of carbon markets

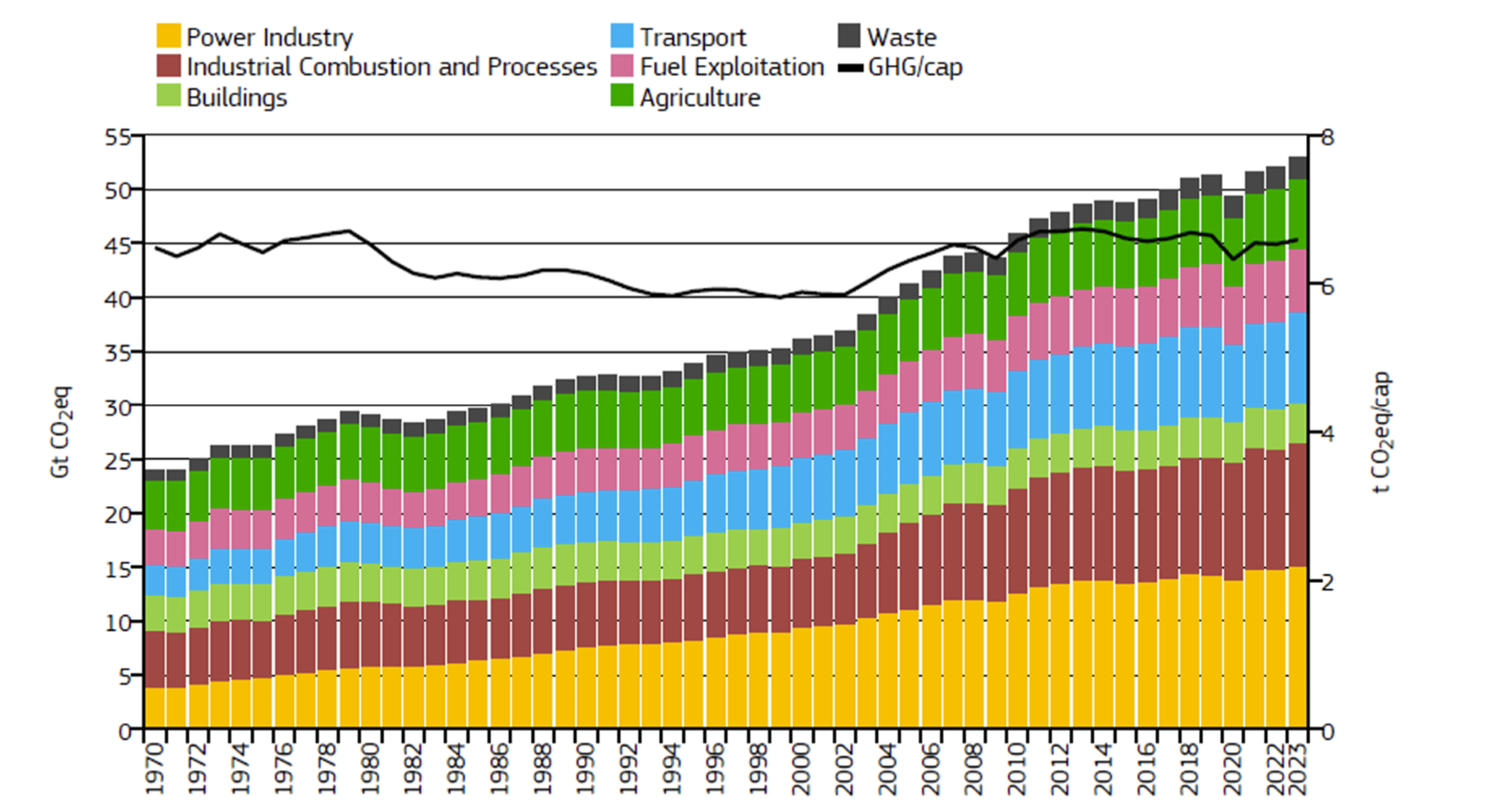

The first major concern is whether carbon markets are genuinely driving down global GHG emissions. While the EU has made significant advances, representing just 6.7% of global emissions as of 2022, total global GHG emissions have continued to rise (see Figure 2). The central question is whether the carbon market facilitates real reductions by major emitters or merely enables offsetting. For instance, credits purchased to offset emissions are less impactful than actual investments in emissions reduction technologies. Consider a project that prevents deforestation: while it generates credits for preservation, it doesn’t actively remove new carbon from the atmosphere. Therefore, if these credits are purchased by companies simply to meet regulatory requirements rather than reduce emissions in production, the market falls short in contributing to overall emissions reduction.

The issue of additionality is also a concern. Which projects do really contribute to the reduction of emissions? For instance, if a wind farm in the Netherlands was likely to be built due to EU incentives or market demand for greener energy, it cannot claim additionality. Limiting the supply of credits to only net carbon sequestration projects (such as new carbon capture) would reduce market size but increase its credibility, as each credit would represent a real reduction. Without ensuring additionality, carbon markets may undermine emissions goals and dilute the environmental impact of carbon offsets.

Another challenge is double counting, where both the project host and credit purchaser claim the same emissions reduction. For example, a reforestation project in Brazil that absorbs CO₂ and sells carbon credits internationally counts its emissions reduction toward Brazil’s national targets. If a company in Spain purchases these credits, the reduction may be doubly counted, overstating global progress and undermining the credibility of carbon markets under the Paris Agreement.

Ensuring that carbon credits reflect true ecological benefits such as biodiversity would improve market credibility

Price volatility in carbon markets further complicates matters, by weakening the price signal needed for long-term investments. For example, after the 2008 financial crisis, an oversupply of allowances in the EU ETS caused a drastic price drop from €30 to €10 per tonne of CO₂, discouraging investments in sustainable technologies like renewable energy and carbon capture. Similarly, recent economic and political uncertainty in Europe caused spot prices to fall from €105.73 per tonne in February 2023 to €66 per tonne by November 2024, potentially jeopardizing the EU ETS’s role in incentivizing sustainable investments. A carbon price floor, establishing a minimum price per tonne of CO₂, may be needed to stabilize prices and encourage companies to invest in emissions-reducing technologies.

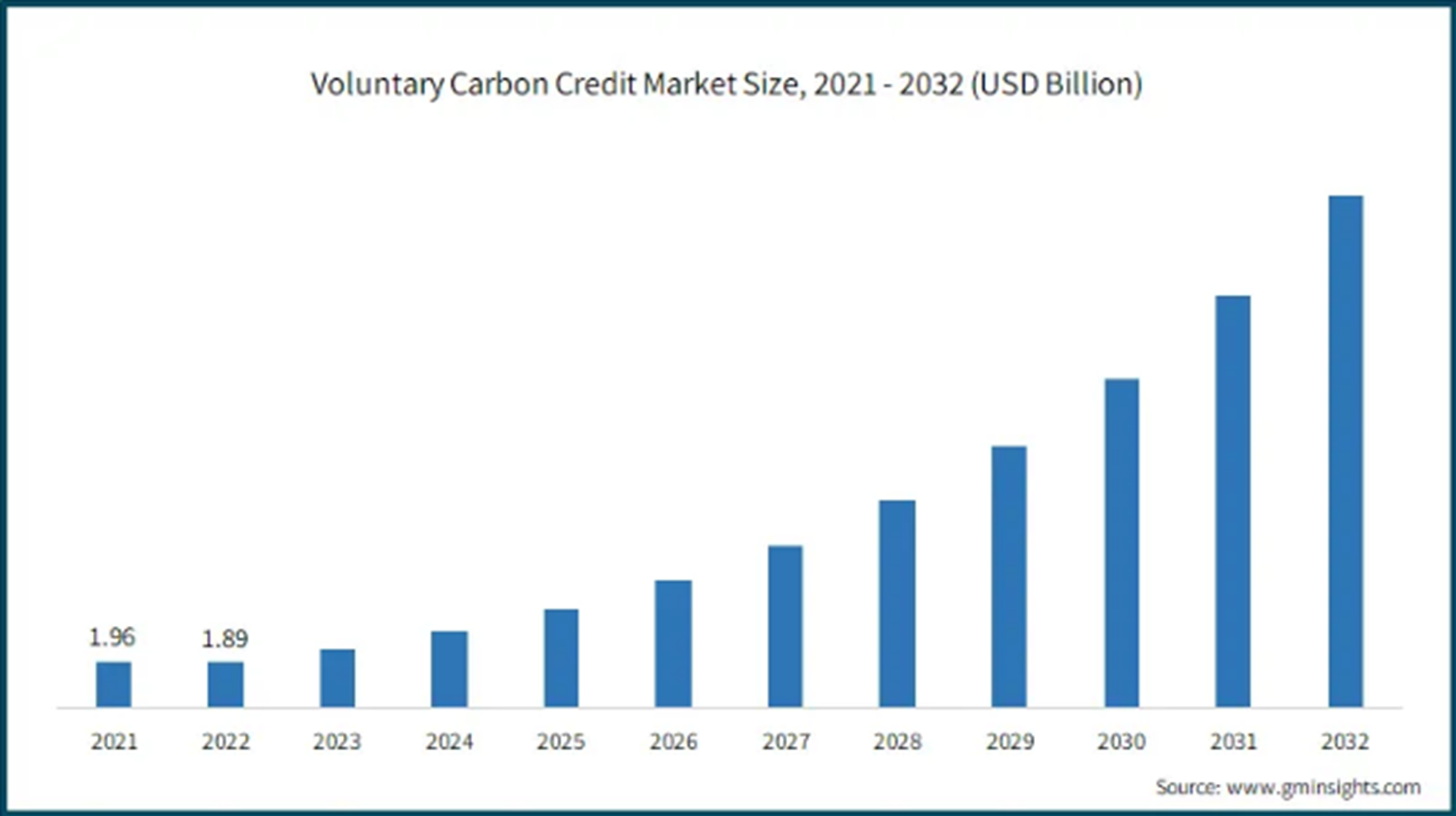

The development of voluntary carbon markets could further add to pricing opacity. To ensure transparency, a significant effort is required to create standardized pricing mechanisms and improve market oversight, particularly as voluntary markets are expected to grow rapidly in the coming years (see Figure 3).

Furthermore, the time horizons of buyers and sellers differ substantially. Companies purchasing carbon credits need immediate offsets to comply with regulations or meet sustainability goals, whereas projects generating these credits often operate on much longer timelines. For instance, projects like reforestation or ocean-based carbon sequestration may take 15 to 30 years to reach full sequestration potential, extending well beyond the immediate requirements of many companies. This disparity raises questions about the future value of these credits and their alignment with the shorter-term targets of the Paris Agreement.

Finally, credit quality and homogeneity are also crucial. Different types of credits offer varying benefits; for instance, a reforestation project using fast-growing eucalyptus trees might sequester carbon quickly but does little to enhance biodiversity and may even harm long-term soil quality. Unlike diverse forests, monoculture eucalyptus plantations contribute less to ecological health and may eventually release stored carbon as they decay. Ensuring that carbon credits reflect true ecological benefits, such as biodiversity and soil health, would enhance the market's credibility and effectiveness in achieving broader sustainability goals.

The way ahead

These challenges highlight the need for improved regulatory frameworks, standardized verification processes, and the integration of robust technology solutions. Addressing issues like additionality, double counting, and price volatility is essential for carbon markets to operate effectively as tools for global emissions reduction and climate resilience.

Despite these challenges, carbon markets offer substantial potential to drive sustainable development and meaningful climate action. By incentivizing investments in renewable energy, conservation efforts, and other low-carbon initiatives, carbon markets can stimulate economic growth while contributing to emissions reduction. With strategic reforms, these markets have the power to catalyze a transition to a more sustainable and resilient global economy.

Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Finance and Accounting at Esade

View profile

- Compartir en Twitter

- Compartir en Linked in

- Compartir en Facebook

- Compartir en Whatsapp Compartir en Whatsapp

- Compartir en e-Mail

Do you want to receive the Do Better newsletter?

Subscribe to receive our featured content in your inbox.