Do we live in a democratic world?

Democracy is in decline around the globe. Its robustness is affected by both the new international backdrop and the failings of governments regarding the provision of social wellbeing.

Democracy is one of the most talked-about issues in political thought because of the lack of consensus about its basic characteristics, which stem from its different models and the variety of scenarios in which it exists – an indication of the complexity of this concept. However, despite this lack of consensus, democracy must be regarded as the best form of political organization because it enables the will of the people to be respected whilst upholding a rule of law and a division of powers able to prevent the abuse of power by those in government, unlike authoritarian regimes.

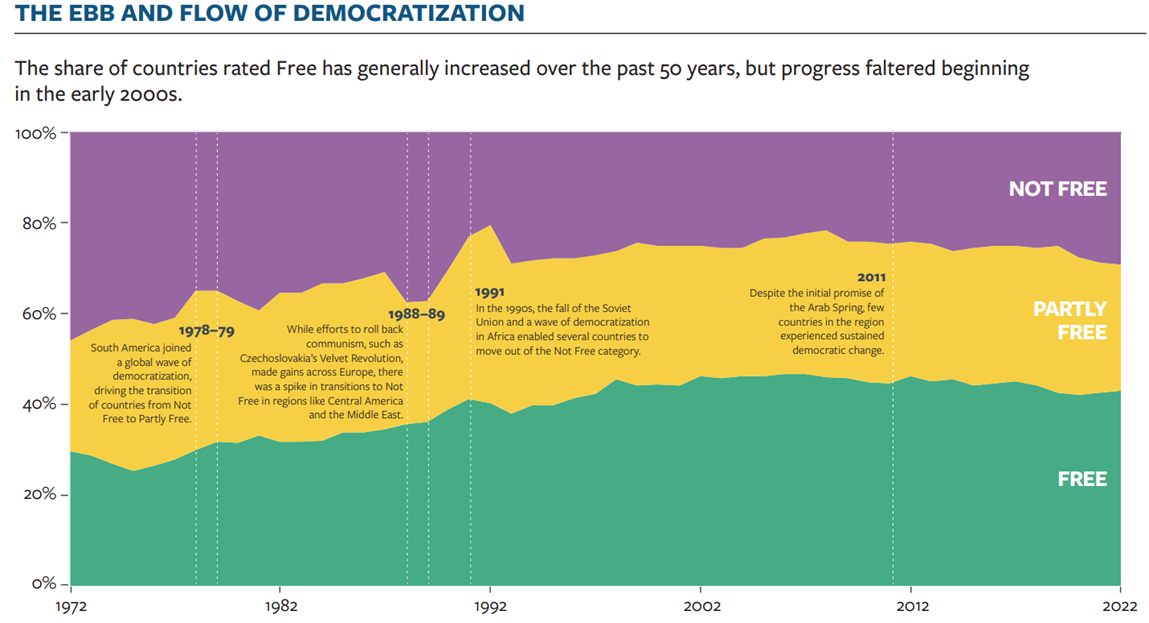

The current state of democracy is not, however, very heartening. According to the latest report by the NGO Freedom House, the number of countries rated free rose from 40 in 1975 to 88 in 1998, i.e., from 25% to 46% of all the countries in the world. But, according to the same source, in this century the number of countries rated free has fallen to 84, i.e., 43%. These data confirm the slight downturn in the concept of democracy as an ideal government model, referred to by some as democratic regression, i.e., the decline in the public’s faith in it, and by others (the most pessimistic) as the end of democracy (Diamond, 2008; Battison, 2011; International IDEA, 2022).

All of which begs the question: why is democracy declining around the globe? There are several possible reasons. One is that it would be difficult for the countries rated non-democratic in the late 90s to become democracies because of their economic and cultural traits that hamper its implementation (Daimond, 2015). Obvious examples of this are North Korea and Iran. Another explanation is that some countries that have adopted democratic models have been mistakenly rated as democracies (Levitsky & Way, 2015). Examples of this problem include some countries where the granting of suffrage enabled the regime to be rated as a formal democracy despite the persistence of autocratic powers, institutions and attitudes at odds with the people’s will, as in the case of Viktor Orban and his party FIDESZ in Hungary.

Another important reason, in my opinion, is the impression that democracy in the West has lost considerable credibility and legitimacy as a form of government to be adopted by developing countries. Many surveys reveal that citizens of Western countries are very unhappy and frustrated about what they regard as their governments’ inability to remedy economic inequality, provide minimum social services and end corruption.

The failings of democracy

What we should, however, be asking is what lies behind these interpretations of the shortcomings of democracy.

One essential factor is the inability of democratic governments to solve social issues. As Daimond (2015) and Fukuyama (2015) point out, they have not achieved economic well-being and fall short in the provision of the public and social services needed by the population, in addition to public insecurity and persistent corruption. As a result, Fukuyama argues that “the legitimacy of many democracies around the world depends less on the deepening of their democratic institutions and more on their ability to offer quality governance.” This is confirmed by the International IDEA report (2022), according to which almost half of the 173 countries assessed suffered a decline in one or more of the metrics used to measure their democratic quality. Furthermore, the establishment of technocratic governments, based on technical knowledge and rationality, has depoliticized democracy, thereby devaluating it and eliminating the discussions and disagreements that are an essential part of any democratic regime (Brugué, 2020). At the same time, these governments have shown themselves to be unable to solve social issues.

In this respect, the incapacity of governments in democratic regimes explains citizens’ disenchantment with political parties and institutions and the representation crisis they have undergone, which has shifted from political indifference and apathy to citizens organizing protests to express their indignation. As confirmed by Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, protests around the world have more than doubled from 2017 to 2022. At the same time, citizen participation in the election processes of their parliaments has fallen. As the following graph shows, participation in the elections of members of parliament has fallen in most European countries, except Hungary, the Netherlands, Poland, Sweden and Switzerland.

Thus, this growing social disenchantment with democratic institutions and their legitimacy as an ideal government model has caused, firstly, greater activism amongst civil society and the creation of non-governmental organizations to solve social issues. This is the case of the Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca in Spain and TECHO in Chile. Secondly, it has triggered an upsurge in far-right parties, thereby eroding democratic practices with populist discourses supposedly seeking to re-establish democracy on the basis of the unity of the leader and the people aiming to discredit traditional political leaders. In fact, populism, through voting, has deteriorated the role of democratic institutions as a fundamental framework for calm, reasonable public debate in which all social groups must be represented.

A struggle on a global scale

Against the backdrop of an international order characterized by a multi-polar distribution of power, a struggle is being waged between the great powers for global leadership and hegemony in parallel with a struggle between two models of government: democratic and authoritarian. Hence the importance of preventing the pressure from authoritarian regimes, the influence of the far right within well-established democracies and the poor management by governments of resources for improving citizens’ well-being from succumbing to greater influence from the authoritarian model.

This should worry us because, as International IDEA (2022) points out in its report, 50% of countries rated non-democratic were becoming significantly more repressive in 2021. Furthermore, in the last 6 years, more countries have shifted towards an authoritarian model of government than towards a democratic model: the quality of democracy fell in 26 countries, and only improved in 13.

In fact, it is very important to prevent the authoritarian model from being more appealing to developing countries simply because they want to forge alliances with the strongest side or leader in a complex multi-polar world with a fragile balance of power. This could happen if China won the challenge with the United States for world leadership. After all, the Asian country has shown that it can achieve economic prosperity without the need for democratic reforms, and can also offer economic support to developing countries regardless of their type of political regime, as in the case in some African countries.

On the contrary, the economic crisis that the West suffered in 2008 had a huge political impact on Western democracies, provoking a legitimacy crisis of the post-Cold War liberal consensus that gave rise to national-populist movements and parties that undermined the credibility of projects such as European integration or free trade. Examples include the Finns’ Party (Perussuomalaiset Sannfinländarna) which participates in the Finnish government but is anti-EU, and Donald Trump’s slogan “America First”, which casts doubt on the idea of free trade. Democracy is, therefore, in a vulnerable state that jeopardizes its legitimacy as an ideal model of government and casts doubt upon the stability of the international order of tomorrow.

Capitalism and democracy

All this makes me wonder how capitalism has contributed to this situation. To answer this question, we can take the democracies of Europe and the United States as an example because they are rather disconnected from democratic values as a result of the great concentration of wealth and the huge economic inequalities that they feature. In this respect, because capitalism is unable to mitigate economic inequalities it prompts a disconnection from the political realm, focusing only on the constant accumulation of personal wealth and subordinating community relations and public interest in a way that undermines the importance of the democratic model and causes considerable political polarization. Consequently, capitalism based on neoliberal ideology does not help strengthen democracy, but does stoke the confrontation between democratic and authoritarian models of government.

Which brings us to the last question: what can we do to prevent the decline of democracy around the globe? To answer this, we must consider how global governance can contribute by means of mechanisms to reduce economic inequalities and create economic and social well-being. By this I mean that all levels of government, from local to international, should be encouraged to take part. In addition, it is very important for democratic regimes to enable civil society to participate more directly in political decisions. It is not enough for civil society to be represented in parliaments by political parties. It is very important to have mechanisms that enable citizens to oversee and scrutinize the actions of their political leaders and ensure that they abide by the law. I am convinced that it is the best way to make proposals that foster democratic regimes that have greater social legitimacy and contribute to a more democratic international order. We must not forget that the consensus of all social groups translates into the widespread will of the people to be able to act. Democracies must, therefore, make dialogue, consensus and participation at all levels a priority in order to consolidate themselves as the system of government best able to remedy social problems and create social wellbeing.

Academic Assistant, Department of Society, Politics and Sustainability at Esade

View profile- Compartir en Twitter

- Compartir en Linked in

- Compartir en Facebook

- Compartir en Whatsapp Compartir en Whatsapp

- Compartir en e-Mail

Do you want to receive the Do Better newsletter?

Subscribe to receive our featured content in your inbox.